Eel Pie Memoriesfrom Comstock Lode No 7 (1980)by Comstock Lode editor John Platt[click on pics to open full-size image in new window] That quotation comes from George Melly's wonderful autobiography. 'Owning Up' and refers to an island in the Thames usually approached from, and associated with, Twickenham, a West London suburb approximately 12 miles from the City Centre. Eagle-eyed readers will no doubt be aware that up until this issue I resided in beautiful downtown Twickenham and that before that had always lived pretty much in the area. Even now I've only moved about 5 miles down river to Chiswick. The purpose of all this preamble (and I know you've been getting impatient for me to get to the point) is that ever since I started this rag, and indeed before that, I'd wanted to produce some sort of historical survey of the post war musical and related activities of the area, which loosely amounts to the towns along the Thames starting (nearest London) with Putney; then Richmond (both on the Surrey side), Twickenham (on the Middlesex side) and Kingston (back on the Surrey side) plus a few less important adjacent places. All of which may sound a trifle parochial - not so! In terms of the musical and social activities that took place in (as some would have it) the 'Thames Valley' (this puts it on a symbolic par with the 'Mississippi Delta' or indeed the less prosaic 'Bay Area') - it was, in the 50's and 60's, as important an area in its own way as Soho, Liverpool or San Francisco. The area has never really been given the recognition it deserves; this then is some attempt at correcting that. The reference to Soho is not gratuitous. Many people from the Richmond/Twickenham areas were involved with the goings on in Soho. This article, then, is linked with the one in the last issue and together they form a general picture of those days. There is no way I can relate a detailed history of all the various places or personages that made up the scene over a twenty year period. Although I'll try and work in most of them (God knows how) I thought the best thing would be to take what I considered the most important part of the whole thing - Eel Pie Island - and deal principally with that. At its best, the 'Island' (afficionados never used the 'Eel Pie' prefix) was the most imaginative, original, wonderful, exciting and enjoyable environment I've ever experienced ('club' - which it was - is far too narrow a word); and in terms of what it set out to do, and largely succeeded in, was unique, certainly in England. Firstly however a little historical background....... The name 'Eel Pie Island', was a purely Nineteenth Century affair, probably arising from the dubious comestibles of that nature sold at the Island Tavern, later the Eel Pie House and Hotel. Earlier names included 'Twickenham Ayte', 'Goose Eyte' and 'Church Ayte'. Believe it or not there had also been a bowling alley on the island in the Seventeenth Century. |

|

Even after becoming a club there was never any advertising. The nearest they ever had was a slip of paper with a list of the following month's bands, more for information than advertising. Nonetheless as its reputation grew they were discovered not just by the local bohemian population but also the Teds as well. Trouble seemed inevitable. One night a gang arrived but were told by Arthur that they weren't accepting any new members at that time. However they saw through that. The gang leader (the head Ted, so to speak) replied 'What you mean is, if I come in there'll be bovva. You're right. They're lippy, ain't they? But they can't fight, so I hits 'em, don't I?' Undoubtedly a very fair description of what would take place. Strangely once Arthur admitted that this was indeed why they were refused entry into the club, the Teds were quite happy. It didn't always end that way. After a few broken windows and noses they noticed a pattern emerging. A group would come over, have one drink, order a second and start looking round for something 'interesting' to do. After a few occurrences they realised that if the police were called as the group arrived, just as they were starting their second drink the police would mysteriously arrive and shepherd them off the Island. In fact this became standard practice in all the local clubs and pubs and prevented a lot of problems. An interesting side effect though was that quite often a Ted, who the previous week had been thrown out as part of a gang would reappear on his own and after a few weeks of drinking in the hotel would eventually be absorbed into the club on the understanding the membership did not extend to his friends. This prevented the culture of the club being swamped by the extremely tense Ted culture, where for someone to touch you was justification for a fight, as opposed to being able to relax and knowing that if you brushed against someone they would probably apologise. To digress slightly, the main Ted hangout at the time was The Boathouse at Kew Bridge, just down the road from here. The Boathouse had a terrible reputation, a hard core rock & roll establishment where fights were a nightly activity. Gangs of Teds from as far away as Southall would have pitched battles with rival gangs from Chiswick and Acton. Later, at the end of the 60's it became notorious again as a skinhead gathering place. In the early 70's it closed, was pulled down, and now there are luxury town houses on the site. Musically the Island was almost completely trad jazz orientated - double bass, tuba, drums, banjo (of necessity - the guitar and piano in the beginning indicated mainstream) and a front line of clarinet, trumpet and trombone, from which line-up very few bands in their right minds ever deviated. Although unique in other ways, the Island, even in its earliest days, wasn't the only jazz club in the area. The Thames Hotel at Hampton Court opened within a week or two of the Island. Kingston had a number of jazz clubs in the late 50's. The Fighting Cocks was reckoned to be the best (it's now the Southern Surplus Store); there was also the Jazz Cellar and the Jazz Barge. The latter was simply a barge on the Thames owned by one Ian Sheridan, then as now an antiques dealer of er..... flamboyant disposition, from Kew. The Barge was a nice try but obviously far too small to be commercially successful. Talking of Kew, in the very early days there was a coffe bar with a 'skiffle cellar' actually on Kew Green, which had connections with the Island. I wonder what the locals made of that. Richmond itself had the Maddingley Club, housed in a big old house on the riverside (technically it's on the Middlesex side and thus in what is known as East Twickenham. Resident there for a number of years were the Keith Smith Band, Smith being an early Colyer enthusiast. The Maddingley has come and gone over the years but could return at any moment and has thus outlasted many of its more famous rivals. By the end of the 50's, fans of modern jazz could go down to The Bull, down by the river at Barnes. The Bull became for many years the centre of modern jazz in the area, with people like Tubby Hayes being regular guests. Actually the Island did try modern jazz (or at least mainstream), when Bruce Turner's band played there. They tried it for about four months but decided in the end it wasn't working. Earlier they had also tried Diz Disley's String Quintet, but that too had failed. Disley in fact was something of a local celebrity. Essentially a guitarist in the Django Rheinhardt tradition, Disley became quite famous in the trad boom days. Melly described him as having 'the face of a satyr, en route to a cheerful orgy'. Raconteur, piss-artist and layabout with distinct anarchist tendencies, Disley had a built-in anti-success formula. He lived locally in East Sheen for many years and played regularly at the Derby Arms on the Upper Richmond Road, a good place but again suffering from being too small. Like the Maddeningly, it comes and goes; they even had Richard and Linda Thompson there a few years ago, when it was a folk club. The Island also ran folk as well, from 1958, much more successfully than their modern jazz experiments. Not surprisingly, folk was very big in the area when it started to boom in the early 60's. The best folk club (or at least the one I have the fondest memories of) was The Crown on the Richmond Road in Twickenham. Regulars early on were Beverley Martin (before she married John - I can't remember her maiden name) and Johnny Joyce, who were in a well known group (whose name I've also forgotten) and lived locally in Twickenham. Everybody that was worth seeing on the contemporary folk scene played there - Jansch, Renbourn, Alex Campbell (whom I seem to recall once called my brother-in-law a "sassenach bastard" for talking in the middle of one of his songs), even the legendary Jackson C Frank played there. Slightly later the immaculately spoken Johnny Silvo ran the club affording us endless renditions of 'Midnight Special' and 'Doctor Jazz'. Later (c 1968) the place featured bands during the extraordinarily dull 'blues boom'. Most were dreadful (Dynaflow Blues Band, 20-20 Blues Band etc) but I did see Free's first (or a very early) gig which wasn't too bad. The Crown had always been a hang-out of Islanders and continued to attract that sort of clientele until they were all suddenly banned (sometime in late '69), and they moved into Central Twickenham to the Cabbage Patch. The Crown was tarted up and employed a lady of grotesque proportions to play the piano and lost 90% of its trade. Getting back to folk, Kingston also had an active folk scene that centered around the 'Folk Barge'. What connection this had, if any, with the Jazz barge, I've no idea. It was however run by an alcoholic called Geoff who drank meths and red wine and who eventually became a traffic warden. It was also the place where John Martyn was discovered. At the end of the 60's there was an active folk club in Richmond called The Hanging Lamp, in the crypt of a church just off Richmond Hill. This again featured all the big names on the folk circuit, plus a few 'others', like the slightly eccentric Ron Geesin, much of whose BBC2 programme 'One Man's Week' was shot at The Hanging Lamp. I must admit that I never liked the place as much as The Crown, perhaps because by 1970 things were just not the same anymore. |

|

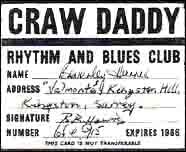

By this stage you may well be wondering what's so special about Richmond and its surrounding area that all these trend setters lived there. Two main factors are involved. Firstly there were, as already noted, loads of art schools in the area, and they as much as anybody in this country evolved the whole bohemian lifestyle. Secondly, what the Richmond area has particularly are large amounts of old varied housing, particularly big Victorian houses that not only offer far more scope for the imagination than a 30's semi or a modern council house, but are also ripe for splitting up into flats. Coupled with this is the fact that Richmond in particular is very attractive environmentally, having none of the inner city problems. It may have been funkier to live in Soho or Notting Hill Gate, but it was a good deal more pleasant to live in Richmond, without actually selling your soul to a suburban way of life. In recent years the indigenous population of the area has become relatively middle class and liberal; back in the 50's and early 60's it was middle class and very conservative. What the area was producing 25 years ago were intelligent kids being forced into a conformity they hated. Thus their rebelliion lay in going to places like the Island and getting into drugs - at that time mainly amphetamines. The big difference between the Island and all the other clubs is that people at the Island, particularly Arthur, tried to do something for them. As early as 1956 they were bringing their problems to him. Because of what was going on at the Island in this respect, various eminent people started dropping in. These included people in the medical field, social researchers, and at least one Home Office researcher [Leslie Wilkins] who had done pioneering work on deviancy. What became obvious to all of them, including Arthur, was that many of the young Islanders, because of their home environment and other factors, were not succeeding in education, not because they were unintelligent, but because they simply did not fit into the usual educational pattern. One visitor to the island developed teaching machines [Gordon Pask]. His basic idea was that standard methods of measuring IQ, ie the ability to think logically, were wrong, and that it ought to be based more on how one adapts to the environment. In tests on his machines, the Islanders came out better than Oxbridge dons. On a more practical level the Island helped members get into Adult Education Colleges, which was far more difficult then. In the end the club supported and funded about 20 people at any one time, which, when one considers that a huge union like the TGWU supports about 3 or 4, wasn't bad. In the end it proved too great a strain on their finances, so they changed tack and eventually persuaded the relevant local authorities to change their grant structures. The Island was always involved in some activity or other. Very early on they formed a group called CARD (Campaign Against Racial Discrimination) and were actively involved in CND. One of their other activities was in supporting young people or groups of young people who had been misrepresented in the press, especially the usual 'beatnik, hair,sex,drugs' syndrome. Often this meant themselves as they acquired an incredible reputation thanks to ludicrously exaggerated newspapers articles. Virtually every child in a 30 mile radius was told never to go to Eel Pie Island. Of course they did then, even if they'd never thought about it before. Newspaper reporting got so bad for young people generally that in 1960 the Island threw a special benefit gig to highlight the problem. Acker Bilk played for expenses, and in the interval various people like MP Frank Allaun and Martin Ennels, then of the National Council for Civil Liberties, spoke. The Times Educational Supplement reported the event and it was discussed in Parliament, as a result of which the first independent member of the Press Council was appointed. How 'evil' was the Island? As Arthur puts it, 'Our major crime was to teach people to think for themselves, an unforgivable sin.' The Island's other activities brings to mind the case of one of its most notable protégés whom I'd better just call Neil. In 1965 Neil was the subject of a book called 'Just Me And Nobody Else', nominally by writer Wilfred De'Ath, but really by Neil. 'A Vivid and Vital Portrait of a Teenager' it says on the cover. Neil was an Island habitué from the very early 60s when he was about 14. After being thrown out of school (Chiswick County, though it's never mentioned - in fact nowhere in the book does it mention locations by name), he ends up working in Twickenham Library (where your editor later worked for a time). One day he finds a cheque in a returned book made out to SEEBOARD (ie the South Eastern Electricity Board) and decides to cash it at the Co-op opposite under the pretext of being Mr SE Board. He is of course caught. Later whilst working at a wine & spirit merchant in Twickenham he is arrested for knocking off Scotch and does three months in a detention centre. On his release he stays at the flat of Arthur Chisnall (known as Albert in the book) who persuades him to write an article based on his experiences for New Society. He does, and as a result meets De'Ath, with whom he does a radio program and later the book. He also ends up on a Home Office Committee concerned with juvenile delinquency. The book is quite fascinating, especially about his life as a beatnik. Actually, although it's not mentioned, Neil shared a flat in Twickenham at one time with Eric Clapton (still known as Eric Clapp) who was trying to learn the guitar from old blues records in Gerry Potter's record shop on Richmond Hill. Gerry is still there, and was for many years a big influence on the scene, having a large stock (and knowledge of) obscure blues and jazz records. Neil also mentions a coffee bar. This, although again not named in the book, is the famous L'Auberge, which was on the opposite corner from the Odeon on the Richmond side of Richmond Bridge. L'Auberge was the place in Richmond to loiter. It was opened in the early 50s by Mr and Mrs Hill, an extremely friendly and quiet couple who ran it very much on the lines of the Partisan in Soho - ie you could just drink coffee, or have a meal, or play chess. It had a wonderfully relaxed atmosphere. The Hills gave it up around '66 when it was taken over by an Italian known as Andy, who became increasingly exasperated with his clientele, whom he never really understood. It lived on until relatively recently, barely resembling the original place, closing earlier and earlier (it used to stay open well past midnight). It's now been completely altered and is an admittedly very pleasant restaurant called Crusts. The only real problem with the L'Auberge was that, especially as the 60's wore on, you were likely to find yourself stoppped and searched by the police (who were parked up the side road) as you walked over Richmond Bridge. It didn't happen every time, just often enough to let you know they knew who you were. I could ramble on about the Richmond police but I'd better not, just to say that the Twickenham police were, by comparison, far more human, and, in their dealings with the Island (except at the end) quite helpful and constructive. For example, in the early days, whenever there was a wedding or suchlike at the club, Arthur would get someone like Ken Colyer's Band and about 500-600 people would march behind New Orleans style, from Twickenham Green down Heath Road to the Island, a distance of about a mile. Arthur would go and tell the police of his intention and they would say, 'You want to take all those people, with all that music, all that way again?' But they always agreed. The marches lasted until about 1960-61 when various things happened not the least of which was the commercialisation of trad by people like Acker Bilk. It didn't seem so much fun anymore. Also within about a year the music began to change. The origins of r&b in England I touched on last time in the Soho piece. Basically it started with Alexis Korner and Cyril Davis at the Roundhouse in Soho in 1956, after which they moved to the Ealing Club (Ealing Broadway Station, turn left, cross at the zebra, and go down the steps between the ABC teashop and the jewellers!). Ealing is only a few miles north of Richmond. Consequently lots of the Island regulars had seen Alexis and Cyril and possibly a youthful Jagger quite early on. How r&b came to Richmond remains rather unclear. Most of the books on the Stones agree the infamous Georgio Gomelsky had been running a jazz club at the Station Hotel opposite Richmond Station for some time before the beginning of '63. Resident jazzband at the Station Hotel (I'm not exactly sure when Gomelsky renamed it the Crawdaddy [ * ] ) were The Confederates led by Dave Hunt, who, deciding he no longer liked jazz, disbanded The Confederates and formed The Dave Hunt R&B Band, who at some point are supposed to have numbered among their ranks Ray Davies of the Kinks. The usual story is that when Dave Hunt's band moved on to 'better things' uptown in early '63, the Stones were called in to fill the gap. |

|

Within six months, the Crawdaddy, bursting at the scenes, moved up the road to the Atheltic Ground where it remained until its closure. It wasn't long after that that the Stones outgrew the club, their place being taken by The Yardbirds. The Yardbirds were essentially a local band; some of them had been to Hampton Grammar (about 5 miles away) and the rest, including Clapton, had been at Kingston Art School. They stayed at the Crawdaddy for about a year when they too moved on. They were replaced by another local band, The Others, who cut one single ('Oh Yeah') before getting their hair cut and going back to Hampton Grammar. They did however briefly reemerge as The Sands in 1967 and played the Saville Theatre. In the late 60's the Athletic Ground put on a series of rock gigs with, amongst others, The Nice, Family, and even Canned Heat on their first tour. The grounds of the Athletic Club were also used between '61 and '65 for the Jazz Festival, although by '63 it included r&b as well. In '66 it moved to Windsor, '68 to Sunbury, '69 to Plumpton Race Course, and then I think it moved to Reading where, of course, it's still held. There were a number of other r&b venues that sprang up locally at the same time as the Crawdaddy. Not surprisingly some, like the Jazz Cellar in Kingston, had been jazz places before, or continued to run jazz as well. Amongst the others were the Toby Jug in Tolworth (who later had Beefheart on his first tour). There was also the Ricky Tick circuit, the main one at that time being out at Windsor, although later they moved into Hounslow, a working class area, about 4 miles from Richmond. The premises they took had held two previous clubs in the 60's (it was opposite the Bus Garage over a car showroom). Early in the r&b days it had been The Attic, where the Yardbirds and later The Others played. That closed down and in 1965 it became the Zambesi, primarily a black club. The Ricky Tick took over late '66 and put on a strange mixture of soul, blues and even bands like the Floyd and Hendrix. The latter was never to the taste of the crowd who by this time were primarily skinheads. It's interesting that in the r&b days mods and beats used to coexist to some extent, their common ground being bands like The Yardbirds. Mods never liked real blues and beats didn't go much on pure soul music, but generally they got on at places like the Crawdaddy. Not so a place like The R&B Club in Feltham. The R&B Club, known to its followers as Benny's, was located in a hall behind the Playhouse Cinema, on the High Street. Soul and Tamla were the order of the day there, although The Hollies played there once. Violence was also a regular feature, and stories like that of the bass player getting worked over for tuning up whilst a Geno Washington record was still playing are legion. |

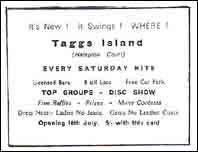

| One of the more interesting but short lived venues was Taggs Island at Hampton. This had an amazing hotel on it built by Fred Karno [The Karsino], resplendent with chandeliers in the ballroom where they held the dances. In the 20's it had been a brothel. There was supposed to have been some sort of curse on it. Sadly the building was destroyed not long after the dances started. |

|

|

Eel Pie Island was not particularly slow to catch on to r&b, difficult not to with the Stones just down the road, and put it on on Sunday nights. Sundays had featured the Island's only ever resident band, The Riversiders, but by 1962 they'd died the death. Amongst the first r&b bands to play at the Island was Cyril Davies' Rhythm & Blues Allstars. Davies played regularly at the Island from then on, and indeed his last gig before he died in January '64 was at the Island. |

|

The slightly loopy Downliner Sect (managed apparently by Don Crane's mother) played often enough almost to justify calling it a residency. For many people though, the most amazing player was Jeff Beck. Originally he was just a member of the Club, but gradually he would start jamming with people or just playing on his own. Eventually he formed his own band, The Tridents, in 1964, who were also Island favourites. They are mentioned in a song about the Island by Andy Roberts (which I can't seem to lay my hands on - I do remember though, that he called the song 'Richmond', when it is definitely about the Island, which is Twickenham). Although out of town bands like The Animals [ ** ] played at the Island, what they were really interested in doing was putting on groups who were going to make it, as opposed to already successful ones. The Island flourished for a further three years through the r&b period. By 1967 however, it was obvious that it couldn't go on as before. Basically they needed at least £200,000 to buy the premises and modernise them. A scheme was drawn up by a young archtect, Brian Phillips, who worked at the Royal College of Art, and a sort of manifesto was produced. It was too much money to ask and the end was in sight. |

|

That more or less ended Arthur's association with Eel Pie Island. Throughout the next year though, plans were being put together by a young local guy, who I remember as being called Grenville, to turn the Island into some sort of arts workshop, which I don't think happened, but he did throw a few private parties there which weren't too bad. In the Autumn of '69 however, the place reopened as a rock club with the ludicrous name of Colonel Barefoot's Rock Garden. It was pretty sleazy in comparison with the old club, a strictly commercial operation featuring those ghastly English rock bands for whom '69 was the big year, Stray, Black Sabbath, Edgar Broughton etc. Half the audience were police in long-haired wigs. Also you had to walk back past the Birds Nest where skinheads used to throw people through plate glass windows for the fun of it. All the atmosphere of the old club had evaporated - no more lying in the summer sunshine on the lawn listening to the band, or being chased by the guy who ran the hotel bar (usually Jack Mars) for doing something illegal. Concurrent with Colonel Barefoot's was the Commune which occupied the hotel. The Commune's founders had some good ideas and for a time it was an interesting experiment. At one stage they took all the door off, and later tried to live in one big room. Interesting but rapidly unworkable ideas. In the end it deteriorated. Most of the people there were just burned out dopers, the atmosphere was extremely tense, busts were weekly occurrences. There were o/d's and suicides. In 1971 they were finally evicted. Almost immediately afterwards there was a fire that destroyed the hotel, leaving the owner with a conveniently empty plot of land to sell. [ *** ] They built town houses on it. Apart from the Island itself, the name lives on, mainly due to Pete Townsend who lives almost opposite the Island on the Twickenham side. There are at least three ventures of his named after the Island. Firstly the record label (in limbo at the moment) who released singles by The Skunks, Straight Eight and No Sweat. The latter were big in Hounslow and Twickenham in recent years and played their extremely unsubtle music in pubs like The Albany in Twickenham and The Red Lion in Hounslow. Then there is Eel Pie music publishing who have the rights to Steve Gibbons' stuff. And lastly there is the book publishing company; so far they've produced mainly children's books, but the new rock division, under the direction of the estimable Peter Hogan, is well under way. It would be nice if I could end this on a happy note and tell you that 1980 is going to be 1966 all over again. You wouldn't believe me and it wouldn't be true. Still Richmond is an attractive place whatever the year is - for the time being at any rate. AddendumBack up in the article I mentioned Andy Robert's song 'Richmond'. Well, last weekend, as it happens (guys and gals) I was down at the Comstock Lode branch office in Cornwall, amongst other things to see the Brainiac 5 in Launceston (and not just to eat Colin 'out of house and home'!). And not unnaturally the subject of Eel Pie Island came up, whereupon 'lonesome Cornish John Cale freak' Mike Venning mentioned the Andy Roberts song , and that he had a copy of it. Here then are the relevant parts -

Various Beck/Island stories were related to me that weekend since in the early/mid 60's numerous Launcestonians were prone to invading London and would hang out not only in places like the Marquee and the 100 Club, but also at the Island and the Crawdaddy, usually ending the evening sleeping (with numerous others) under Richmond Bridge or with the crowds of be-tented foreigners who took over the Island for whole weekends. A remarkable coincidence took place concerning the small ad for Brian Knight (which he gave me) that appeared in the last issue headed 'Blue Lovers', exhorting one to go and see him at the Holsworthy Memorial Hall sometime in 1964. It seems that the Holsworthy Memorial Hall is very close to Launceston, and the ad appeared in the Launceston local rag, owned, as it still is, by Venning's dad. The point of this story is that the guy who ran those gigs used to go up to London and somehow persuaded ace r&b bands to come and play for next to nothing in Cornwall. He managed to get The Pretty Things, Them, and Jeff and The Tridents. It seems that he had seen Beck one wild night at the island, out of his head, playing lying down on the speakers, so out of it that he fell into the audience. He was immediately booked for Cornish parts. Those that saw the Tridents reckon that Beck played better with them than at any other time. Amongst other oddities, he would insert contemporary advertising jingles into the middle of 'Jeff's Boogie'. In Zig Zag No 5, Beck briefly mentions his Eel Pie days. 'I used to play amidst a wash of beer and smelly cigarettes. We used to have a really good time - it was our weekly job... the rest of the week we spent doing nothing... And then all of a sudden, people started turning up in droves - there were 900 one week, which was apparently a record... it reached a stage where we were outdrawing The Yardbirds who were appearing at the Crawdaddy in Richmond.' In the song Andy Robert's also mentions the famous footbridge. In fact it is a great concrete arch spanning the distance from the mainland to the Island, opened in 1957. Prior to that there had been an old chain ferry that you pulled yourself over on. Frequently the boat would vanish, and hordes of inebriated Islanders would swim back to the mainland. Even after the bridge was opened, on hot summer evenings people would still swim back, although as the river became more polluted you had to be fairly pissed to do it. The bridge was just wide enough to drive a Transit over it provided all the band got out and mixed with the hoy-polloy walking over - getting the van stuck on the bridge was a weekly occasion that caused much merriment to the regulars and thoroughly annoyed the old lady in the hut who collected the one (old) penny toll. Ah! those were the days. Article Credits |

| Island photos (except the Hotel) © Mike Peters. Mike is also a jazz musician who played regularly at the Island - as in the picture on the right. His wife, Cy, was Island member No 1. The hotel photo is courtesy of Richmond Libraries - special thanks to Ron Knight. The Crawdaddy and Tagg cards are from the Beverley Harris Collection. Thanks also to Tim Summers. |

|

|

|

* See the video of the Giorgio Gomelsky memorial gig at the Station Hotel in 2016 for an explanation of how the Crawdaddy Club got its name - Weed. ** There is no evidence that The Animals ever performed on Eel Pie - Weed. *** The fire took place while most of the people who were living there were being held by the police following a mass arrest in a nearby pub - it's generally assumed that the two events were connected - Weed. |

||

Comstock Lode covers and summary of contents | John Platt (1952-2001) - obituary

Eel Pie home | music mementos | Eel Pie contacts | Eel Pie Hotel pics